Module 2: Foundations of mathematical thinking

EDUC 315 - Howard University

School of Education

Module Overview

This module introduces foundational mathematical thinking, Polya’s problem-solving method, and the Concrete-Representational-Abstract (CRA) instructional approach. The focus is on understanding how we can support students in developing systematic problem-solving skills and connecting concepts with hands-on learning.

Understanding mathematical problem solving

What is Problem Solving?

The heart of mathematical thinking where students make sense of and solve new problems.

Emphasis on a systematic approach to build students’ confidence and skill development.

George Polya’s Four-Step Method

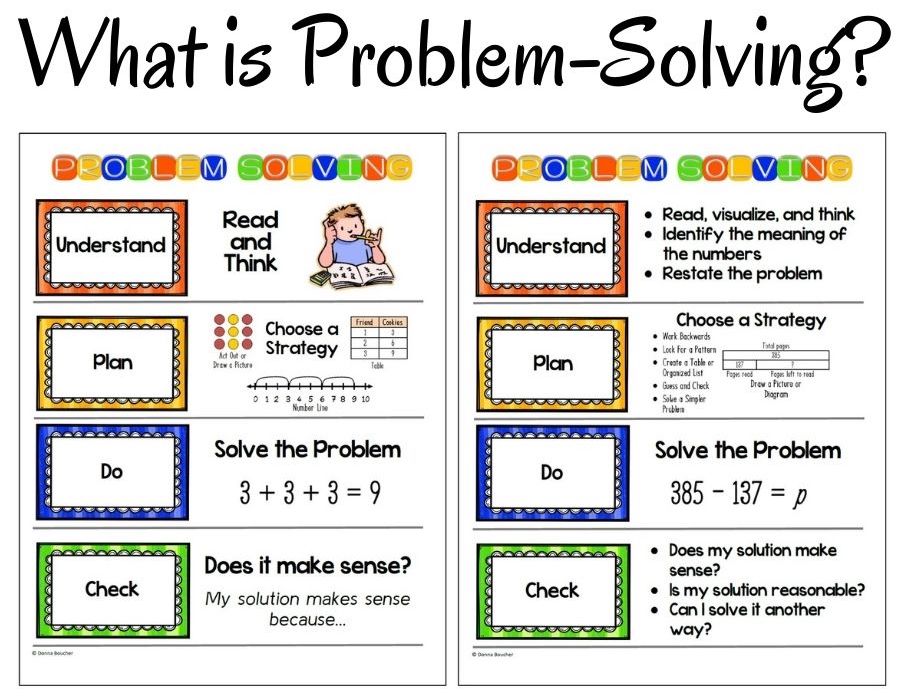

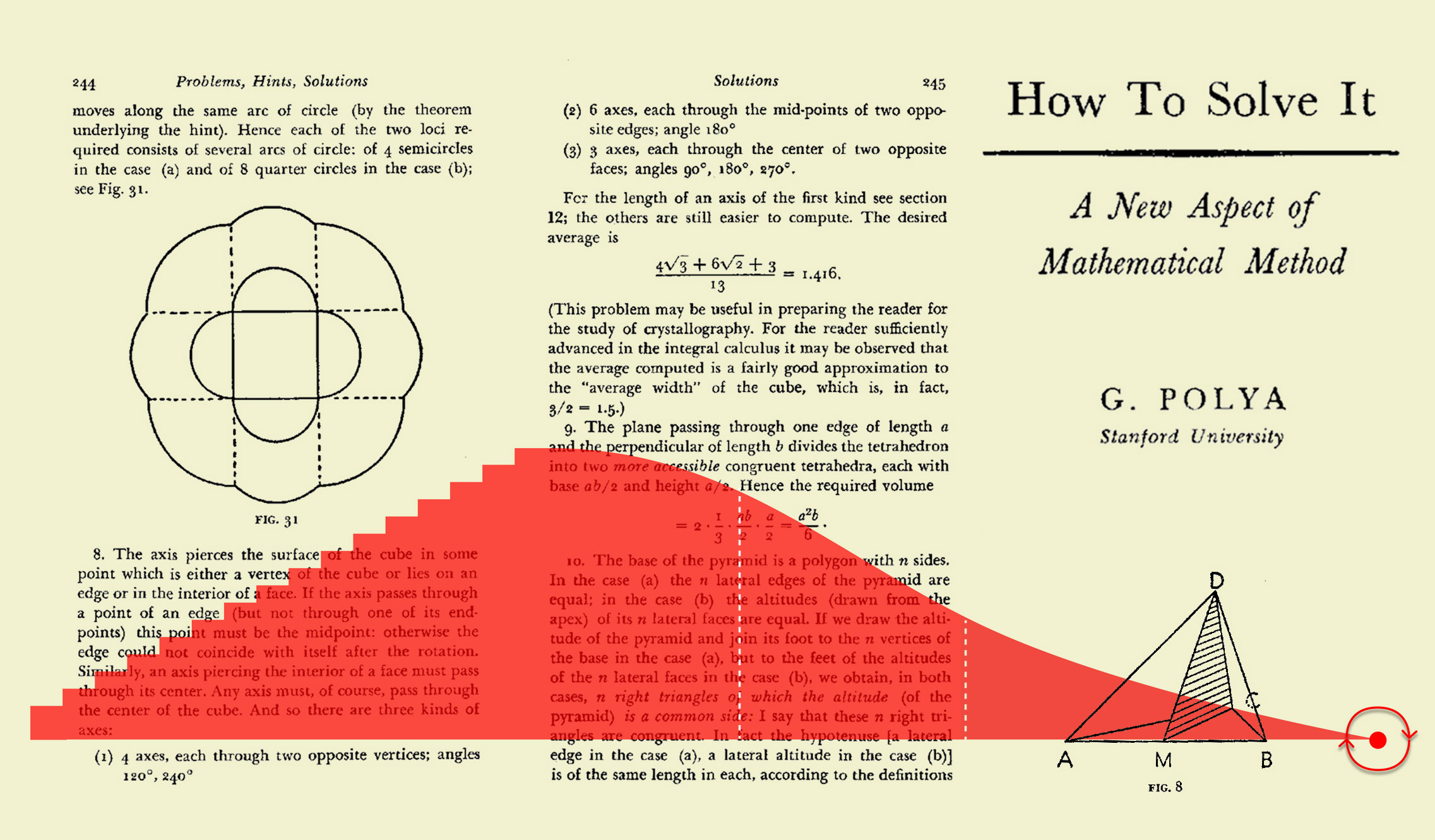

Nearly 100 years ago, a man named George Polya designed a four-step method to solve all kinds of problems: Understand the problem, make a plan, execute the plan, and look back and reflect.

UNDERSTAND THE PROBLEM: Read carefully, identify knowns and unknowns, restate the problem in your own words, and draw pictures if helpful.

DEVISE A PLAN: Think of strategies like drawing diagrams, looking for patterns, working backward, or breaking down the problem.

CARRY OUT THE PLAN: Implement the chosen strategy carefully and check each step for accuracy.

LOOK BACK: Review the solution, check for mistakes, and consider alternative strategies or extensions.

Classroom Application

Practice using Polya’s framing in the development of your mathematics activities.

How can this method can be taught explicitly to students to build metacognition and resilience?

Concrete-Representational-Abstract (CRA)

What is CRA?

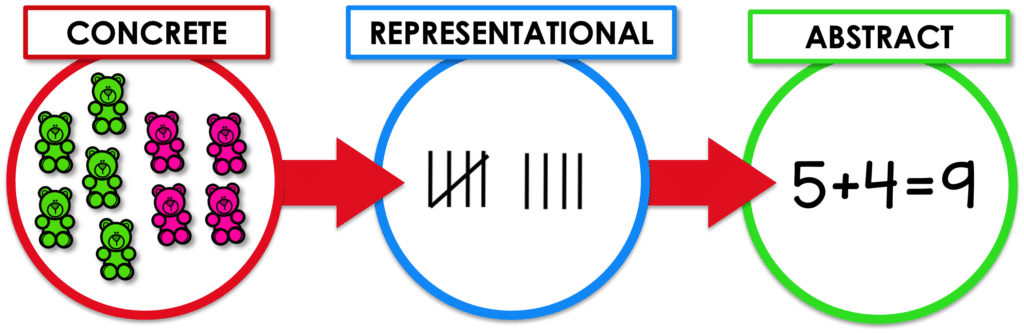

An instructional framework that supports conceptual understanding by moving learners through three stages:

Concrete: Use physical objects or manipulatives (e.g., blocks, counters).

Representational: Use drawings, diagrams, or visual models of concrete objects.

Abstract: Use numbers, symbols, and equations without physical aids.

Why CRA Matters

Builds strong foundational understanding and helps all learners, especially struggling ones.

Encourages deep conceptual thinking and connects tangible experiences to abstract mathematics.

Classroom Applications

Demonstrate CRA with fraction concepts, geometry, or operations.

Use CRA to scaffold problem solving following Polya’s steps.

Connecting Problem Solving and CRA for Effective Teaching

Integrating CRA with Polya’s Problem Solving

Use CRA stages to support the ‘Understand’ and ‘Devise a plan’ steps.

Move students gradually from hands-on experiences to symbolic reasoning as they solve problems.

Developing Logical Thinking

- Introduce sets, number systems, and basic logical reasoning to prepare teachers for promoting mathematical thinking.

Reflection and Discussion

How can you support students struggling with abstract reasoning?

How can CRA and Polya’s method build confidence in math learning?

Developing math activities

Math activities are a necessity in any elementary school classroom!

Math activities may not be complete lessons or units that introduce a new topic but, instead, they can be used provide opportunities for your students to:

Learn new material in a fun and exciting way, or

Complete a different form of a math assessment that is not a test or quiz.

Math activities come in many different formats and they may be based on the amount of time that you have to use, sometimes at the start of a lesson, or on an idea or topic that does not require a full lesson, such as a review of an older topic.

When designing math activities, it is often useful to see what other teachers have done and consider ways to adapt them to your classroom and students. Often, there is no need to recreate the wheel, so make use of online resources and other tools that can give you idea. However, it is important to consider your own needs and priorities when modifying activities.

A good way to think about math activities is the timing, which is often tough with elementary school students. For example, if you have 15 minutes to complete an activity, you want to make sure that students will have ample time to do whatever is required. To that end, less if often more!

When planning a math activity, it is often useful to think about the specific students who will be engaging in the activity (their grade level), timing, and how these components can align with a very specific outcome or goal. For a quick example, consider the SMART goals for a way to think about your outcomes.

What are you considering for your math activity?